By Lisa Aedo

Over the years, I have often wondered what it is that gives rise to different cultures and ways of living on the earth. In Scandinavia, the Vikings built houses with thatched or green roofs and shared them with livestock for protection from the cold climate. This arrangement also provided safe pasture on the roof for a goat or two. In many parts of the world, site selection and landscaping are indicators of worldly status and success, often designed to impress. I remember admiring the designs and plantings in visits to Frogner Parken in Oslo, or Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, and the Versailles in Paris. These royal commissions were all references to the Western world in their day. However, it was when we moved to Peru that I developed a sense of wonder at the size and scope of Inca landscapes and infrastructure.

The engineering feats and community organization that made their built landscapes possible were expressions of a profound understanding of and respect for nature. They also reflected a sense of commitment and responsibility towards the welfare, both physical and spiritual, of all their citizens. Before the conquest in 1532, there was enough food stored to feed the entire Inca population, estimated at over 16 million, for at least seven years. Their road network stretched from today’s Ecuador and Colombia in the North to Chile and Argentina in the South. By building up terraces on the high, steep, Andean mountain slopes they were able to reduce erosion and create level ground for agriculture. These fields were irrigated by using hydraulic engineering principles now used in regenerative permaculture farming. The adaptations made by the Incas to survive in their particular geography and climate gave the land the characteristics now considered typical to that area. There is, however, much more to the landscape than can be seen on the surface. This is the foundation of their cultural landscape.

In the Inca cosmovision, what is in heaven is also reflected on earth. From the vantage point of the lofty Andes with peaks over 20,000 feet high, the Milky Way appears as a river, or “Hatun Mayu” (Great River) in Quechua. In it, the Incas saw shapes and figures like animals that existed in their land and were important or sacred to them.

This river is reflected on earth as the Willka Mayu river (Sacred River) and gives life to the Sacred Valley of the Incas just North of their former capital, Cuzco.

In the Southern hemisphere, the winter solstice occurs on June 21st. As an agrarian culture, this knowledge was important to the Incas because it marked the turning of the seasons and beginning of warmer weather. It enabled them to know when to prepare the land for planting in September when the rainy season typically starts. They celebrated it with Inti Raymi, or feast of the Sun, a highlight in the Inca calendar. Not only did the sun represent warmth, fertility, and prosperity, but also light. This is illustrated in many of the Inca structures that play with the light and shadows created by the path of the sun throughout the day and seasons.

In the Inca culture, the Incas were considered the children of the sun, and represented its power to generate life and wellbeing. With regard to the stratified social structure of the Incas, the chief Inca family served as what we would characterize the highest class in society. The nobility under them were distributed throughout the land as relatives or people with earned privilege, religiosity, and special skills. Under them were what we might call the common people. In this society, there existed a concept of “Ayni”, or reciprocity. It was an understanding that we are all needy at certain times, and that people must help each other when asked. There was also the concept of “Mita” and “Minka”, which represented communal work such as building and maintaining infrastructure including roads, bridges, irrigation canals, and other structures for the benefit of all. It was through these concepts that society functioned. They were true artists on a grand scale in their development of landscape function and design.

Moray, near the Sacred Valley, is an agricultural experimental area that illustrates how the Incas were able to refine and develop plant hybrids that could thrive at higher altitudes and climatic conditions. Specimens would be planted at the lower levels and with each successive season the new seeds were planted at higher and higher terrace levels, taking advantage of the slight change in microclimate at each level, thus allowing the surviving plants to become acclimated to different growing conditions and expanding their cultivation.

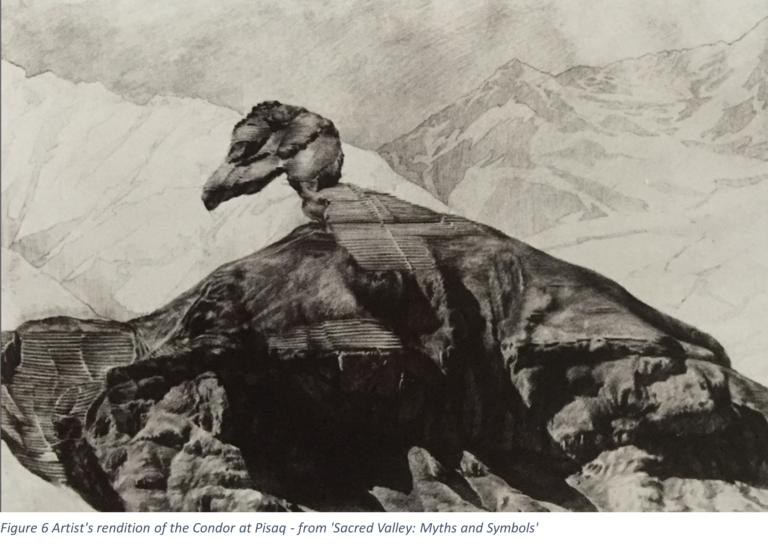

With regard to their spirituality, they considered three “levels” of existence or knowledge: The first was “Hatun Pacha” (Spiritual or high knowledge, often related to the cosmos and symbolized by the Condor); “Kay Pacha” (Knowledge related to the here and now, represented by the Puma); “Ukhu Pacha” (Hidden knowledge or related to the underworld, symbolized by the Snake). What I found fascinating was the Inca’s use of these symbols and important zoomorphic and anthropomorphic forms in their landscape designs. On the road from Cusco towards the Sacred Valley, as one descends towards the village of Pisaq, there is a display of one of these animals:

While not noticeable at first because of the sheer magnitude of the design, the following artistic rendering clearly outlines the head and collar, as well as the outstretched wings of this sacred bird. What is of particular note is that the top of its head is also the location of the temple or most important sacred structure of the design.

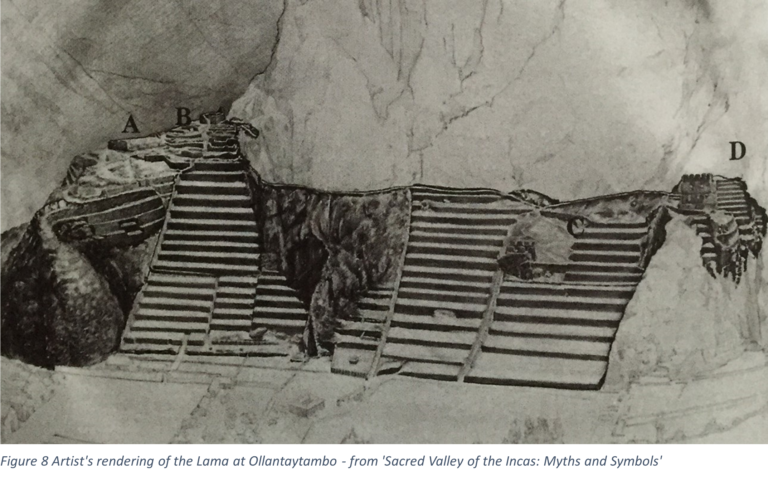

Another example of this type of design is located further down the valley in Ollantaytambo. The mountainside is also terraced, but this time in the form of one of the animals found in the Milky Way or Hatun Mayu.

In this artist’s rendering, we can again see that the head is of special importance. Area “A” contains the most finely crafted stonework and represents the most sacred spot in the design. “B” is in the location of the eye of the animal, and is lit up by the sun at a specific time of the year, possibly as a reminder of an important date in their calendar. Areas “C” and “D” bear relation to the bodily functions of the animal.

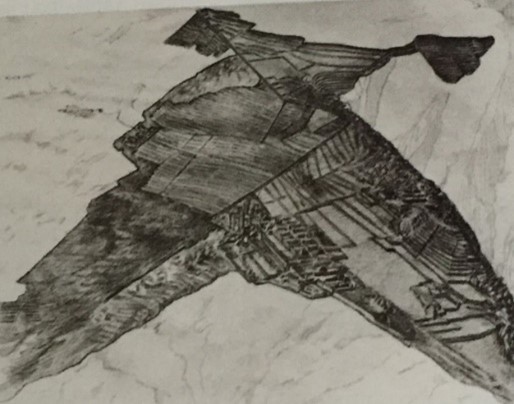

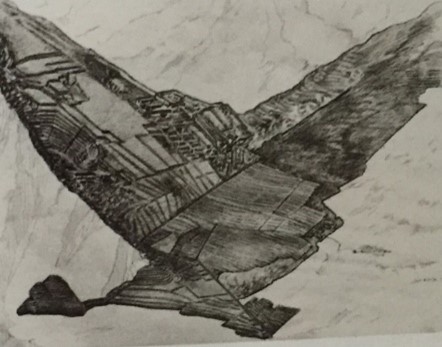

My last example of the Inca’s use of sacred symbolism in their landscape design is well known for its impossible location and inspiring construction. Machu Picchu was one of the last structures built by the Incas. While it is often translated as “Old Mountain”, its name can also mean “Old Bird” in Quechua. With the following illustrations the reason becomes evident. Here it is seen from above, at the top of adjacent mountain Huayna Picchu. The Condor, in Inca mythology, served as the messenger between heaven and earth. As observed, the terrace designs of Machu Picchu form the shape of a Condor in flight. For this reason, Machu Picchu is considered a sacred place of pilgrimage; a sanctuary where people from distant areas would come to make their petitions in the belief that the Condor would bring their messages to heaven.

Throughout the Americas, there is a recurring myth of a cultural hero who helped civilize communities suffering from conflict and ignorance. In Quechua, he was known as Wiracocha; in Aymara, Tunupa. He taught them how to live in peace and work in harmony with nature. After performing many miracles and bringing much knowledge to the people, he left by way of the sea. According to their legend, he promised to return. The native inhabitants of the Sacred Valley say that the 200 foot image found carved in the mountainside at Ollantaytambo is the image of Tunupa.

I marvel at the spiritual expressions left by the Incas and their predecessors. Their legacy reminds me of our mandate to remember who we are and to be good stewards of the earth. Their work with the existing landscape serve as a reminder that as we shape the landscape, it also shapes us. They made the earth productive in ways that also reminded them of the spirituality at the heart of what they did. And all benefited. There is much to learn from other cultures. When we open our minds to mutual understanding, we start filling in knowledge gaps and build on common ground. What the Incas reflect to me in their landscape design and sensitive use of resources is a deep reverence for life and God’s creation. The Incas and their forebears not only built terraces, but also symbols of their spiritual beliefs so that everywhere they looked, there was an object or activity which helped focus on the sacred within.

When I think of my belief in God and Jesus Christ, creators of our earth, and the knowledge imparted from the Book of Mormon about Christ visiting the American Continent and telling the Nephites that he had ‘other sheep’ to visit, I wonder if this might not be one place he visited, and that the Inca predecessors and descendants transmitted these stories for many generations. The legacy of teaching people to live in harmony with each other and performing miracles coincides with what we believe of Christ. In his ‘First New Chronicle of Good Government’, Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala mentions that they (the Incas) knew of Christ before the conquest. They also lived in harmony with nature in ways that showed a deep sense of spirituality and reverence towards nature. Christ’s example to us is grounded in love: Love of God and neighbor, including all His creation. I can only imagine what a difference it would make if we as individuals, communities and nations on earth focused on this simple idea.

Lisa (Jorgensen) Aedo was born in Pennsylvania and grew up in Norway and Switzerland. Her husband, Cesar, is a native of Peru. She has a masters in landscape architecture and currently works as a designer in St. George, Utah.

Note: Blog posts are written by volunteer writers; the opinions of writers are their own and are not necessarily representative of Latter-day Saint Earth Stewardship.

I’m loving the energy and enthusiasm in your work. ❤️